Sample Return from all across the Solar System (KISS workshop)

I was fortunate to be invited to this short course organized by the Keck Institute of Space Studies called “Sample Return from all across the Solar System”. This experience offered me a great opportunity to learn more about the science behind sample return missions and the challenges faced by the scientists and engineers involved in these missions. As an engineer, I’m keen to bridge the gap between engineering and the scientific principles underlying different missions.

This course also resonated with a question that deeply interests me: “Where and how can we discover life within the Solar System and beyond?”

Here’s a brief summary of what I’ve learned:

Talk 1. Past Sample Return Missions and Major Achievements, by M. Zolensky, NASA Johnson Space Center

He gave examples of sample return missions from the Moon:

- Samples from Lunar Near Side: Luna, Apollo, Chang’e missions

- Samples from Lunar Far Side: Chang’e

and talked about some major unanswered questions, such as the nature and amount of water at the south pole, details about the bombardment history, and possible involvement with early life emergence on Earth.

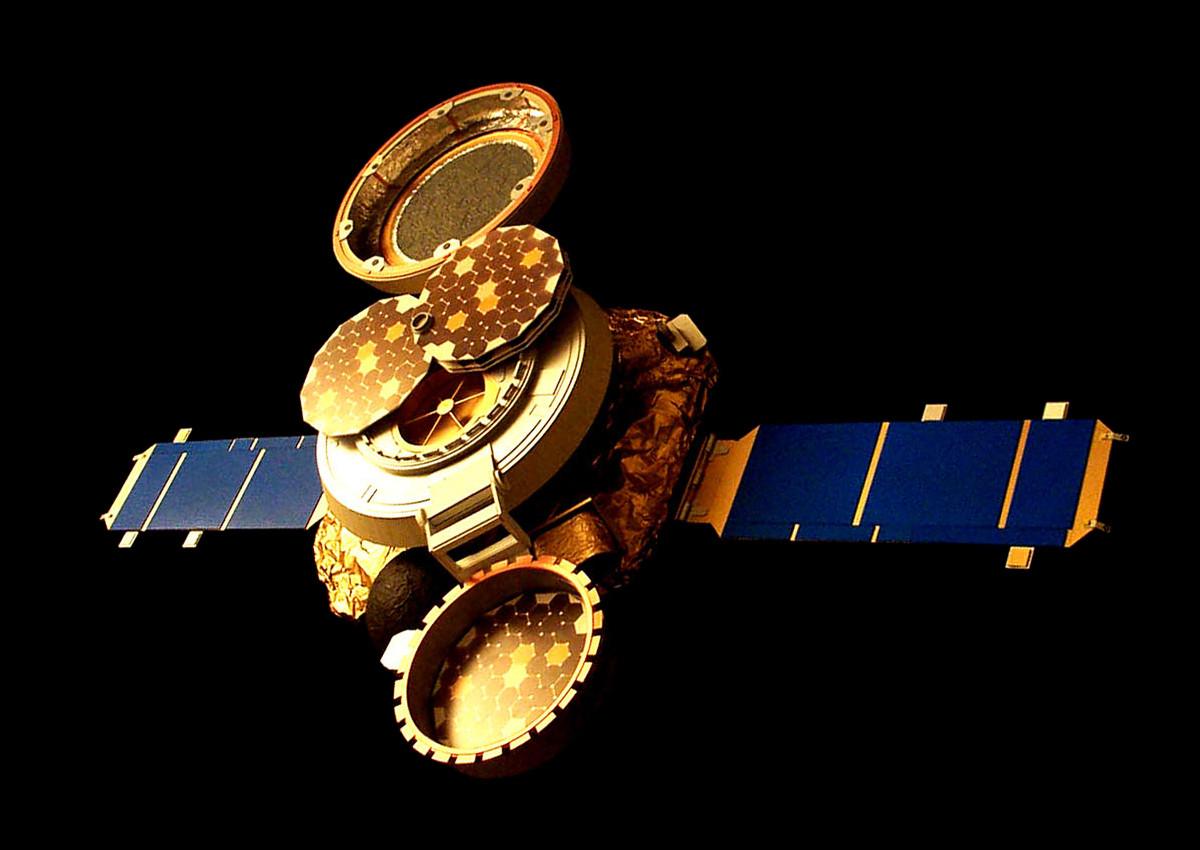

Then, the Genesis mission (figure below) was presented, which was launched in August 2001 to collect solar wind samples and return them to Earth. Some of the major results of this mission include the measurement of O isotope abundances.

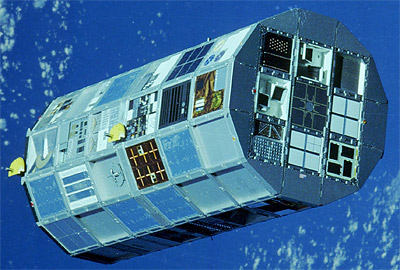

Then, he talked about some experiments that were conducted to collect astroid and comet dust, such as the Long Duration Exposure Facility (figure below). “The Long Duration Exposure Facility, or LDEF, was a cylindrical facility designed to provide long-term experimental data on the outer space environment and its effects on space systems, materials, operations and selected spores’ survival.” It was placed in Low Earth Orbit by the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1984 and was retrieved by the Space Shuttle Columbia in 1990. (source: Wikipedia). There were also some experiments conducted on the ISS, such as the Tanpopo experiments, which used silica gel to collect micrometeorites.

Some examples of astroid sample return missions include:

- Hayabusa recovered < 1g material

- Hayabusa2 recovered 5.4 grams

- OSIRIS-REx recovered 121 grams

Kind of crazy to think how little material was recovered from these missions, but how much we can learn from them. And one important thing to note is that the samples must be returned in a vacuum, as they are extremely reactive to everything on Earth.

Some examples of comet sample return missions include:

- Stardust: 81P/Wild 2

- Rosetta from 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

I also learnt that the “P” in 67P stands for Period comet.

Some other lessons learned: samples must be returned in an airtight container. Hhe health and safety should be the primary mission priority, sample analysis techniques continue to evolve, team membership should be very inclusive and flexible and samples will be extremely reactive to everything on Earth.

I really love learning about all the different space missions and the science behind them. When I was in high school, I had this challenge with myself to learn by heart all the different NASA missions to date.

Talk 2 “Linking the protosolar disk with the inner Solar System”, by Prof. François Tissot.

He started by presenting the different types of meteorites:

- Stony meteorites, from crusts/mantles

- Iron meteortites, from cores

- Stony-iron meteorites

- Chondrites (figure below)

He talked about isotope anomalies. There were quite some details that were hard to follow for me, because I am not a geologist, but I got the general idea. Maybe I should do a 3rd Masters in geology.

He also mentioned that Venus return missions are very important. I also learned about the chrondritic model, which models the composition of Earth. Scientists are arguing whether this model is correct or not. Also, that isotopic anomalies are very important for understanding the formation of the solar system.

Talk 3 “Dynamical Evolution” by Prof. Karen Meech

I really wish I would have attended this talk, but I had to attend another meeting at that time. I will try to find the recording and watch it.

Talk 4 Ocean Worlds and Habitability, by Prof. Jonathan Lunine

Some of the facts I learned from the talk are below:

- Oceanworld are bodies with substantial liquid water on their surfaces or within their interiors. They are very interesting for astrobiology.

- Habitability requires that three or four general conditions be met: energy, appropriate physical and chemical conditions, solvent, and elemental requirements.

- Conditions for abiogenesis is still a mystery (habitability bottleneck).

- Types of measurements to require habilitability: geophysical, chemical, isotopic, and electromagnetic.

- The oceans of Europa were discovered by a magnetometer on Galileo.

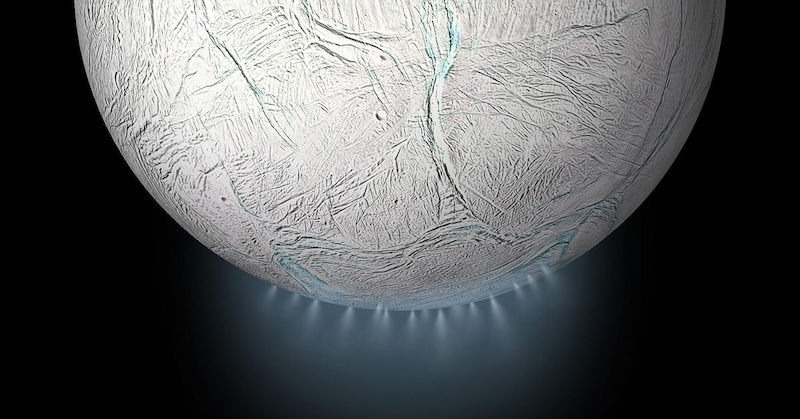

Saturn’s moon Enceladus (figure below) is one of the easiest to explore. There is evidence of an ocean. There are organics in the Enceladus ocean, but their identity is not known. There is evidence there is redox chemistry in the ocean of Enceladus.

Europa Clipper will orbit Jupiter and make 50 fly-bys of Europa. For ocean worlds, present-day habitability can be established by in-situ measurements.

I liked that he presented both pros and cons for sample return missions.

Talk 5 - Ices in the Outer Solar System and their Connection to the Protoplanetary Disk, by Prof. Mike Brown

I didn’t know, but during the early solar system, the planets were closer together. He also showed and explained us plots of reflectance spectra (reflectance vs. wavelength), which was very interesting to see.

I also realized I wish I would know more about chemistry.

Source of the images: The internet

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: